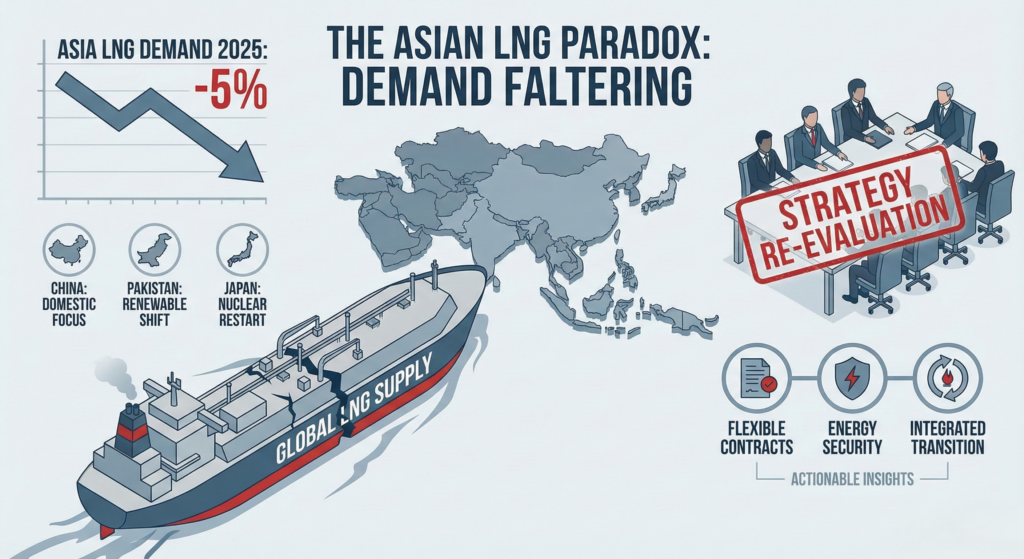

The global narrative around Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) has been simple: Asia is the engine of growth, an insatiable market that will absorb every molecule the West can supply. This has underpinned final investment decisions (FIDs) for billions of pounds worth of liquefaction capacity worldwide. However, recent data suggests a starkly different, and far more complex, reality is unfolding. Asia’s LNG demand is poised to experience a significant contraction in 2025, a development that must be urgently addressed in every boardroom from London to Singapore.

Challenging the Bullish Consensus

The International Energy Agency (IEA) and other bodies have consistently projected Asia to account for half of all global natural gas consumption growth. Yet, the latest figures indicate that the region’s LNG demand is set to fall by around $5\%$ this year. For C-suite executives, this is a red flag. It’s not merely a cyclic downturn; it suggests structural shifts in market behaviour that challenge the core assumptions built into long-term investment models.

The largest contributor to this surprising contraction is, predictably, China. Escalating geopolitical tensions, coupled with the imperative for absolute energy security, have spurred Beijing to drastically reinforce its domestic energy base. China’s LNG imports have fallen by a reported $16\%$. This is being achieved through a multi-pronged approach: increased domestic gas production, greater reliance on pipeline imports from Eurasia, and aggressive, state-backed deployment of solar and wind power. For business development managers banking on exponential growth in China, this pivot towards indigenous sources is a fundamental re-rating of their market opportunity.

Beyond China: A Region-Wide Pattern

Crucially, the demand faltering is not limited to just China. Key emerging markets are also demonstrating significant price sensitivity, a trend often underestimated by suppliers focusing on long-term fixed contracts.

- Pakistan, once heralded as a prime growth market, is increasingly sidelining LNG in its national energy strategy due to years of unaffordable import costs. An unexpected boom in small-scale residential and commercial solar installations is displacing gas-fired power generation, demonstrating that decentralised, renewable energy solutions are now directly competing with centralised LNG imports.

- Japan, despite being one of the most mature LNG markets, is also seeing a moderate decline in consumption. This is a direct consequence of restarting idled nuclear reactors and the continuing build-out of its renewable energy portfolio, reducing the reliance on gas as a transition fuel.

These regional examples underscore a vital lesson for executives: the perceived inelasticity of Asian LNG demand, especially in the spot market, is a fallacy. Consumers and policymakers will switch fuels, and they will delay projects if the economics do not align with their national priorities.

Actionable Insights for Strategy and Investment

What does this paradox mean for the C-suite in charge of global strategy and the business development teams tasked with securing future revenue? It necessitates an immediate re-evaluation of three key areas:

- Contractual Flexibility: The market clearly favours flexibility. Producers must move beyond rigid, long-term, destination-restricted contracts. New deals must incorporate provisions for price reviews that are more responsive to regional spot market realities and allow for greater destination flexibility, enabling buyers to trade cargoes and mitigate their own price risk. This shared risk approach will be essential for locking in the next generation of Asian buyers.

- The “Energy Security” Premium: Geopolitics has re-entered the equation with force. National Oil Companies (NOCs) and state utilities are increasingly willing to pay a premium, or accept a different energy source altogether, if it improves supply certainty and reduces dependence on distant, politically exposed suppliers. Business development should be leveraging partnerships, joint ventures, and technology transfer that directly support the buyer’s domestic energy independence objectives, shifting the conversation from a simple commodity transaction to a strategic national partnership.

- Integrating the Transition: This drop in LNG demand is intrinsically linked to the parallel rise of renewables. Executives must acknowledge that LNG’s bridge fuel role is becoming shorter and more contested. Future gas projects must be planned with robust, bankable pathways for decarbonisation, such as integration with Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) or the eventual blending with hydrogen. Projects that ignore the accelerating and price-competitive transition risk becoming stranded assets far sooner than current models predict.

In conclusion, the Asian LNG market is transitioning from a story of simple, voracious growth to one of sophisticated, strategic diversification. Success in this evolving landscape will hinge not on optimistically projecting past trends, but on a pragmatic and agile strategy that embraces contractual innovation, aligns with national energy security goals, and integrates the growing competition from an increasingly cost-effective renewables sector. This is not the end of Asian gas demand, but it is certainly the end of business as usual.

The contrasting fortunes of two major deals—Saudi Aramco’s increased stake in MidOcean Energy and ADNOC’s withdrawal from the Santos acquisition—mark a definitive pivot in the region’s corporate strategy. We are moving from an era of unchecked asset accumulation to one of tactical, risk-adjusted partnerships.

The Santos Wall: Valuation Meets Regulation

The withdrawal of the $19 billion bid for Australia’s Santos Ltd by XRG (an ADNOC subsidiary) and its consortium partners is the most significant M&A correction of 2025. While officially attributed to “commercial disagreements” over valuation, the deal faced substantial headwinds that every BD leader in the region must recognize.

- Regulatory Friction: Acquiring a strategic national asset in a Tier-1 jurisdiction like Australia is becoming increasingly difficult for sovereign-backed entities. The scrutiny from foreign investment review boards is intensifying, adding a “political risk premium” to any full takeover bid.

- Operator Risk: Becoming the operator of record for assets like Santos’s Barossa or Gladstone LNG projects invites direct exposure to local environmental activism, labor disputes, and tax regime changes. For a Gulf NOC, this operational drag can outweigh the strategic value of the reserves.

The MidOcean Model: The Proxy Play

Contrast this with Saudi Aramco’s approach. By increasing its stake in MidOcean Energy to 49%, Aramco is essentially effectively “outsourcing” its M&A engine.

MidOcean, managed by institutional investor EIG, acts as a specialized vehicle. It acquires the assets (like interests in four Australian LNG projects and Peru LNG), manages the regulatory approvals, and handles the operational partnerships. Aramco, as the major shareholder:

- Secures the Offtake: Gaining access to the LNG volumes for its growing trading desk.

- Limits Exposure: Avoiding the direct “sovereign buyer” label that complicates deals in Western markets.

- Deploys Capital Efficiently: Gaining exposure to multiple geographies (Latin America and Asia-Pacific) for a fraction of the cost of a single corporate takeover.

Strategic Drivers: Volume Over Vanity

This shift is driven by a fundamental realization: You don’t need to own the well to trade the gas.

For MENA executives, this signals a change in the flow of outbound capital. The “Checkbook Diplomacy” of buying entire companies is fading. It is being replaced by sophisticated joint ventures, equity-light offtake agreements, and investments in agile midstream vehicles.

Key Takeaways for Business Development:

- Target the Vehicle, Not the Asset: If you are selling into this market, structure your deals as partnerships or minority equity opportunities rather than full divestments.

- The Trading Desk is King: The ultimate goal for both ADNOC and Aramco is to feed their trading arms. Any deal that brings flexible LNG volumes (destination-free cargoes) will be prioritized over fixed-asset acquisitions.

- Jurisdiction Matters: Expect capital to flow away from “difficult” regulatory environments (like Australian M&A) toward more transactional markets or US Gulf Coast brownfield expansions where offtake financing is king.

The failure of the Santos deal is not a retreat; it is a refinement. The Gulf’s capital is still looking for a home in the global gas market, but the terms of engagement have strictly changed.

For energy executives operating in the region, this standoff is not merely a diplomatic row; it is a material disruption to the supply/demand balance of North Africa and a signal that geopolitical risk is re-pricing regional infrastructure assets.

Context: The Interdependency Trap

The deal in question was designed to solve two problems simultaneously. Israel has a gas surplus and limited export routes (no LNG facilities of its own). Egypt has a gas deficit, soaring domestic electricity demand, and idle LNG export capacity at Idku and Damietta.

- The Plan: Chevron and its partners committed to investing heavily to expand Leviathan’s production and build a new offshore pipeline (Nitzana route) to bypass existing infrastructure bottlenecks.

- The Reality: Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu paused the approval process in late 2025, linking the gas deal to broader security negotiations regarding the Gaza border and Sinai.

This politicization of the molecule flow breaks the “commercial shield” that has largely protected the Israel-Egypt gas trade from political volatility over the last five years.

Risks: Capex, Counterparties, and Credibility

The immediate casualty of this pause is investor confidence.

- Stranded Capex Potential:

The expansion of Leviathan Phase 1B and Phase 2 requires Final Investment Decisions (FIDs) worth billions. These FIDs are predicated on firm offtake agreements. If the Egyptian offtake is uncertain, the partners (Chevron, NewMed, Ratio) cannot greenlight the upstream capex. The “November 30” deadline was a critical gate for these decisions; passing it without resolution puts the entire project timeline in jeopardy.

- Egypt’s Energy Fragility:

Egypt is already grappling with power shortages. The government had factored these incremental Israeli volumes into its 2026-2030 power generation strategy. If this gas does not arrive, Egypt faces two expensive choices:

- Increase reliance on fuel oil for power generation (higher emissions, higher cost).

- Import more LNG from the global spot market, draining foreign currency reserves.

- The LNG Re-Export Model:

Egypt’s strategy to earn hard currency by re-exporting Israeli gas as LNG to Europe is effectively paused. This denies Cairo a critical revenue stream needed to service its sovereign debt and stabilize its currency.

Upside Scenarios and Strategic Pivots

Is the deal dead? Likely not. The economic logic remains overwhelming for both sides.

- The “Grand Bargain” Scenario: History suggests that energy often becomes the sweetener in larger diplomatic deals. A resolution to the security disputes could see the gas deal approved as part of a broader normalization package. If unlocked, the project could move fast, with the partners likely prioritizing the new pipeline to recover lost time.

- Alternative Routes: This friction may accelerate Israel’s exploration of alternative export routes, such as the long-discussed pipeline to Turkey or a Floating LNG (FLNG) facility. For BD executives, this opens new potential engagement channels: if the Egypt route is deemed too politically risky, technology providers for FLNG could see renewed interest from Israeli operators.

Executive Takeaway

The paralysis of the Leviathan expansion serves as a case study in political risk management. For companies investing in MENA cross-border infrastructure, the lesson is clear: Commercial viability is necessary, but insufficient. Contracts must include robust buffers for political force majeure, and supply portfolios must be diversified. Until the valve is politically reopened, the Eastern Mediterranean remains a high-beta energy market.