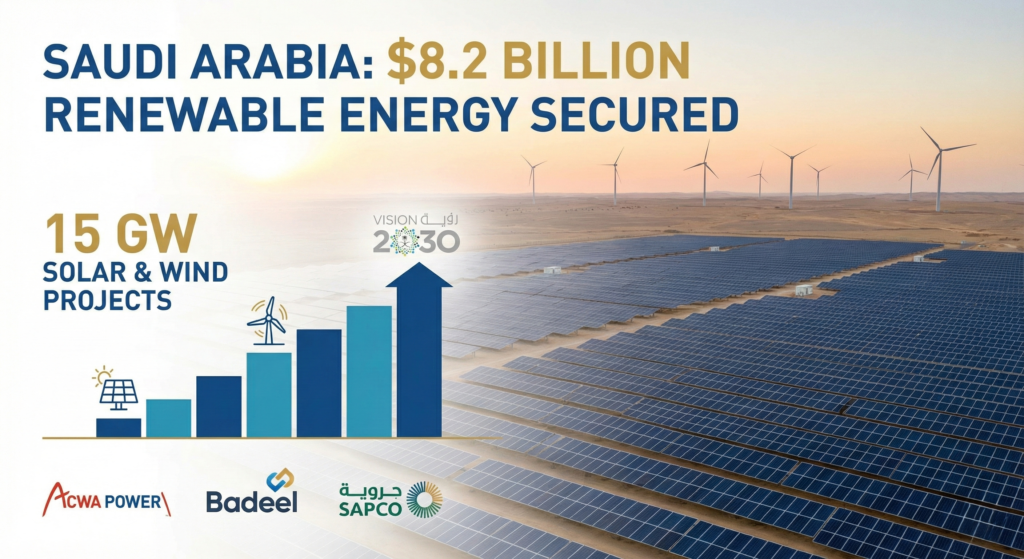

Saudi Arabia has successfully achieved financial closure for a landmark portfolio of seven large-scale solar and wind projects, injecting $8.2 billion into the Kingdom’s grid overhaul. The deal, announced on December 2, 2025, de-risks a substantial portion of the nation’s ambitious clean energy transition under the Saudi Green Initiative and Vision 2030.

This massive capex deployment, led by a consortium of national champions including ACWA Power, the Water and Electricity Holding Company (Badeel), and the Saudi Aramco Power Company (SAPCO), confirms the Kingdom is moving aggressively from aspirational targets to hard infrastructure. The cumulative capacity of the seven projects—12 GW of solar and 3 GW of wind—is expected to be fully operational between the second half of 2027 and the first half of 2028.

Context: Policy, Supply, and Financing Dynamics

The deal is a direct manifestation of the policy commitment laid out in Vision 2030, which aims for 58.7 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2030. This push is driven by two primary factors:

- Freeing Up Oil for Export: By using low-cost domestic renewables to meet soaring local electricity demand (driven by cooling and desalination), the Kingdom maximizes the volume of high-value crude oil for export, improving state revenues.

- Global Decarbonization Leadership: The development is key to Saudi Arabia’s goal of achieving net-zero emissions by 2060.

The financing structure itself sets a new precedent for financing mega-projects in the MENA region. The Public Investment Fund (PIF), through its subsidiaries, played a central role, underscoring the sovereign commitment that significantly reduces perceived risk for international lenders and investors.

Upside Scenarios for BD Leaders

The financial commitment to 15 GW creates immediate, tangible opportunities across the entire project lifecycle.

I. Grid and Transmission Investment

Integrating 15 GW of intermittent power requires a massive upgrade to the existing grid. This deal signals forthcoming tenders for high-voltage direct current (HVDC) links, advanced battery energy storage systems (BESS), and digital smart grid management technologies. Firms specializing in power market stabilization and transmission infrastructure are now entering a multi-year boom cycle in the Kingdom.

II. Localization of Manufacturing and Services

Saudi Arabia’s Industrial Development Fund (SIDF) and its in-country value (ICV) programs are tightly linked to these mega-projects. The sheer scale of demand for solar PV modules, wind turbine components, and steel for racking systems creates a compelling business case for establishing local or regional manufacturing bases. For instance, a major precedent for localization is seen in the broader hydrocarbon sector, where global drilling and service companies have long partnered with local firms to meet Saudi Aramco’s ICV requirements. This model is now being directly applied to the green economy.

III. Hydrogen and Water-Energy Nexus

The development of vast, cheap renewable power acts as the direct enabler for the Kingdom’s ambitious green hydrogen and ammonia projects, such as the flagship NEOM facility. This 15 GW capacity will not only serve the domestic grid but will also likely underwrite future industrial decarbonization initiatives, including powering large-scale reverse osmosis desalination plants, directly addressing the water-energy nexus. By securing the low-cost power supply, the commercial viability of green commodity export is strengthened.

Risks and Mitigating Precedents

While the financing is closed, executives must be mindful of execution risks.

- Supply Chain Inflation: The global market for PV components and specialized construction labor remains tight. The size of the Saudi projects risks driving up regional pricing. Prudent strategy involves securing long-term master supply agreements (MSAs) with tier-one suppliers now.

- Talent and Capacity: Delivering 15 GW on a tight timeline—2027/2028—will stress the local Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) capacity. Project developers must strategically utilize global EPC expertise while integrating local subcontractors to comply with ICV mandates. This balancing act is critical for timely delivery.

- Offtake Certainty: The Saudi Power Procurement Company (SPPC) will offtake the entire capacity. This government-backed Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) structure offers robust revenue certainty, a key de-risking element that attracts international financing. The precedent of state-backed PPAs in the UAE’s Al Dhafra Solar PV project showcases the high-security of these agreements.

The $8.2 billion financial closure is not an endpoint; it is the starting gun for the most significant energy infrastructure buildout in MENA history. The strategic focus must shift to execution excellence, supply chain resilience, and maximizing in-country value to capitalize on this multi-year opportunity.

For energy executives operating in the region, this standoff is not merely a diplomatic row; it is a material disruption to the supply/demand balance of North Africa and a signal that geopolitical risk is re-pricing regional infrastructure assets.

Context: The Interdependency Trap

The deal in question was designed to solve two problems simultaneously. Israel has a gas surplus and limited export routes (no LNG facilities of its own). Egypt has a gas deficit, soaring domestic electricity demand, and idle LNG export capacity at Idku and Damietta.

- The Plan: Chevron and its partners committed to investing heavily to expand Leviathan’s production and build a new offshore pipeline (Nitzana route) to bypass existing infrastructure bottlenecks.

- The Reality: Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu paused the approval process in late 2025, linking the gas deal to broader security negotiations regarding the Gaza border and Sinai.

This politicization of the molecule flow breaks the “commercial shield” that has largely protected the Israel-Egypt gas trade from political volatility over the last five years.

Risks: Capex, Counterparties, and Credibility

The immediate casualty of this pause is investor confidence.

- Stranded Capex Potential:

The expansion of Leviathan Phase 1B and Phase 2 requires Final Investment Decisions (FIDs) worth billions. These FIDs are predicated on firm offtake agreements. If the Egyptian offtake is uncertain, the partners (Chevron, NewMed, Ratio) cannot greenlight the upstream capex. The “November 30” deadline was a critical gate for these decisions; passing it without resolution puts the entire project timeline in jeopardy.

- Egypt’s Energy Fragility:

Egypt is already grappling with power shortages. The government had factored these incremental Israeli volumes into its 2026-2030 power generation strategy. If this gas does not arrive, Egypt faces two expensive choices:

- Increase reliance on fuel oil for power generation (higher emissions, higher cost).

- Import more LNG from the global spot market, draining foreign currency reserves.

- The LNG Re-Export Model:

Egypt’s strategy to earn hard currency by re-exporting Israeli gas as LNG to Europe is effectively paused. This denies Cairo a critical revenue stream needed to service its sovereign debt and stabilize its currency.

Upside Scenarios and Strategic Pivots

Is the deal dead? Likely not. The economic logic remains overwhelming for both sides.

- The “Grand Bargain” Scenario: History suggests that energy often becomes the sweetener in larger diplomatic deals. A resolution to the security disputes could see the gas deal approved as part of a broader normalization package. If unlocked, the project could move fast, with the partners likely prioritizing the new pipeline to recover lost time.

- Alternative Routes: This friction may accelerate Israel’s exploration of alternative export routes, such as the long-discussed pipeline to Turkey or a Floating LNG (FLNG) facility. For BD executives, this opens new potential engagement channels: if the Egypt route is deemed too politically risky, technology providers for FLNG could see renewed interest from Israeli operators.

Executive Takeaway

The paralysis of the Leviathan expansion serves as a case study in political risk management. For companies investing in MENA cross-border infrastructure, the lesson is clear: Commercial viability is necessary, but insufficient. Contracts must include robust buffers for political force majeure, and supply portfolios must be diversified. Until the valve is politically reopened, the Eastern Mediterranean remains a high-beta energy market.